Books We Loved, Nov. 2019

- C. P. Lesley

- Nov 15, 2019

- 4 min read

Updated: Mar 14, 2020

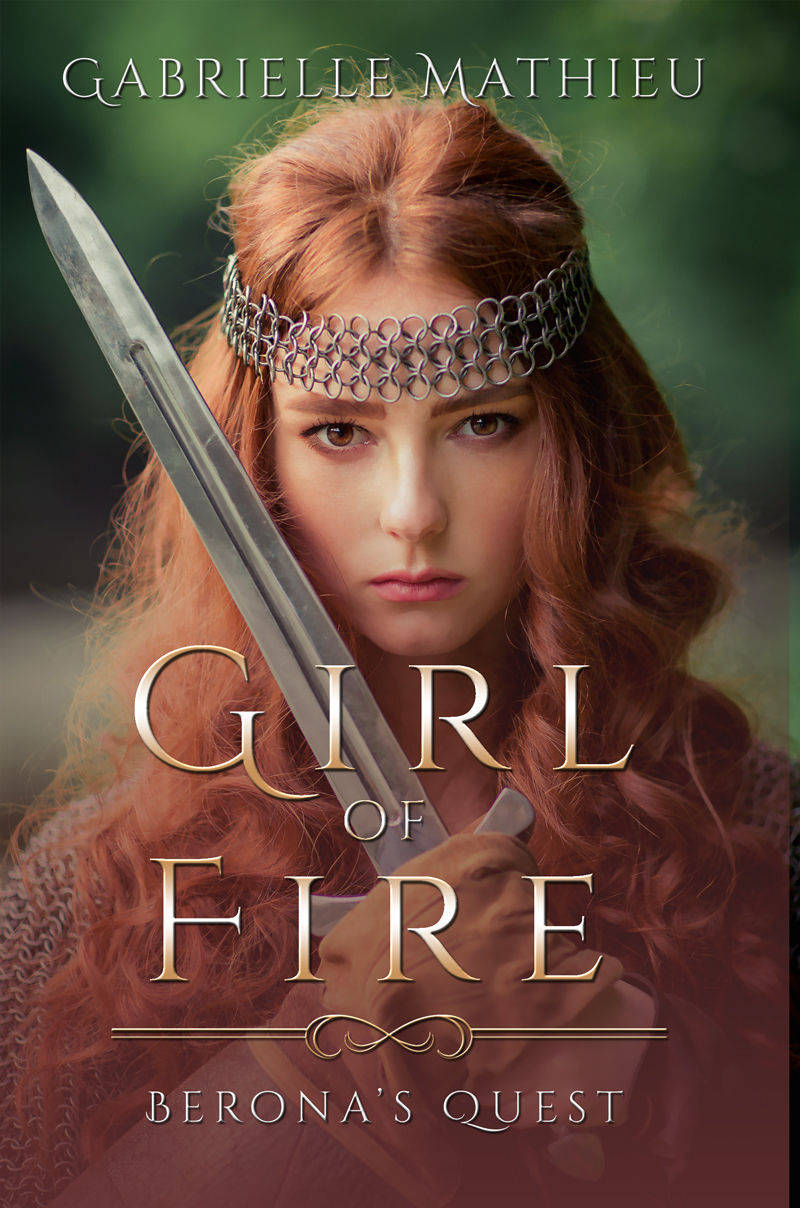

Here are three novels we particularly enjoyed this month. But don’t stop there. We also published two new books of our own this fall, so in addition to Joan Schweighardt’s Gifts for the Dead (Rivers 2) and these three wonderful novels, do make time in your schedule for our latest new release, Gabrielle Mathieu's Girl of Fire, hot off the presses as of November 3, 2019. You can find out more by clicking on their book titles, which will take you to their individual book pages on this site. There you can read and listen to excerpts as well as see summaries and reader endorsements.

Joseph O’Connor, Star of the Sea (Mariner Books, 2004)

That a story devoid of heroes, set against the grim background of the Irish famine, can be so moving and compassionate, is a testament to the skill of the extraordinary novelist Joseph O’Connor. A book within a book, Star of the Sea is written as if it were an investigation of actual events on the coffin ship of the same name. (Coffin ships were the vessels used to transport the starved and desperate Irish who fled to America. Many died in the overcrowded holds).

O’Connor’s narrator is one G. Grantley Dixon, a failed writer with liberal leanings, hoping for fame—literary history is brought alive in the chapter titles and various typefaces that harken back to the times of the Dickensian novels and their exploration of social issues. The American descendant of slave owners, Grantley, is eager to cast the Anglo-Irish landowner, Lord Merridith of Connemara, as an exploitative landlord—all the more so because Grantley is in love with Merridith’s neglected wife. The reality is more complicated—and more tragic.

At the beginning of Star of the Sea, we learn that Lord Merridith is targeted for murder, and meet his killer. With each subsequent chapter the reader is drawn into the skein of relationships and vengeance that binds the killer and his victim, both men of Connemara.

A brilliant and meticulous account of monumental suffering, O’ Connor’s work is saved from sheer despair by flashes of ironical humor and moments of individual courage. Highly recommended.—GM

Gill Paul, The Lost Daughter (William Morrow, 2019)

The brutal murder of not only Russia’s last emperor, Nicholas II, but his entire family and remaining staff in July 1918—a crime committed by Bolsheviks worried that the approaching White Army would free the royals and restore them to the throne—still invites speculation more than a century later. Rumors that one or more of the children escaped have circulated since the news first broke—and persevere despite the recovery of DNA from bones and scientists’ assurances that everyone has now been accounted for. So the idea that Grand Duchesses Maria and (earlier, in the same author’s The Secret Wife) Tatiana escaped unharmed doesn’t really hold up.

But there are better reasons to read this novel than the possibility of a royal escape. After a detailed examination of the imperial family’s life in imprisonment, including the guards who both helped and killed, The Lost Daughter follows Maria from captivity through the heady political world of early Bolshevism, the increasing terror of the Stalin years, and the horrors that accompanied the Nazi Siege of Leningrad. By the time we reach the 1970s and the reconstruction of Peterhof, Peter the Great’s playground on the shores of the Baltic Sea, we’ve enjoyed an intimate and fascinating excursion into a vanished world.

Sure, Maria could be anyone who survived those turbulent decades of revolution and war. But imagining what it would be like for the daughter of the Russian Empire’s former autocrat does give the story a pathos that it might otherwise not achieve. And unraveling the links between Maria’s experiences and the modern-day story that begins with a young Australian woman hearing from her dying father the words, “I didn’t want to kill her,” is a satisfying puzzle all on its own.—CPL

Diane Setterfield, Once Upon a River (Atria Books, 2019)

It is the longest night of the year, the Winter Solstice, sometime in the late 1800s, and the regulars are gathered, as they always are, at the Swan Inn on the Thames River, where they expect to eat, drink and entertain one another with ever more enticing stories. Setterfield barely finishes her description of this setting when the inn door bursts open and a blast of freezing air is followed by a man—a stranger, badly bleeding—carrying a child who is clearly dead. Who is the man? He collapses before anyone can find out. Who is the child? And how can it be that she arrived dead—everyone saw her—and some hours later she is breathing?

The frequenters of the Swan could not have asked for a more exhilarating focal point for their gathering, on that night and on all the nights that follow. The “miracle” is all they can talk about, especially when it is revealed that three different parties are claiming that the child, who is mute and can’t speak for herself, belongs to them. Any one of them could be telling the truth: the wealthy couple from down the river, the family of the man who deserted his child and her now-deceased (drowned) mother, or the local parson’s housekeeper, who believes the child to be her younger sister.

Once Upon a River is as fluid and beguiling as the river it unfolds beside (and often on or even in). It is full of twists and turns and glorious movement. Sometimes it floods. Its plot and characterizations and ideas are as deep and rich as any riverbed. Setterfield is a master storyteller. Her book is magical and spellbinding. It definitely warrants multiple readings.—JS

Comments