Books We Loved, Aug. 2025

- Five Directions Press

- Aug 14, 2025

- 5 min read

And here it is, the middle of August already—still summer, officially, for another four or five weeks, but with the return to school on the horizon for many families, it doesn’t feel that way for everyone. This month’s “books we loved” post offers a diversion from the approaching change of seasons by opening windows onto three very different worlds, two historical and one historical fantasy. But all of them are a perfect match for your remaining long and lazy days.

Carys Davies, Clear (Simon & Schuster, 2025)

There are, in Clear, two crises going on in Scotland in the mid-1800s. The first is the 1843 Disruption, marked by a number of evangelical ministers breaking with the Church of Scotland in protest over British intrusion into their religious affairs. The second, known as the Highland Clearances, saw wealthy landowners forcibly removing tenants from their rural and sometimes island homes in regions the landlords deemed better suited (i.e. more profitable) for sheep grazing.

Clear unfolds at the intersection of these two historical moments. John Ferguson, one of the fleeing ministers, is dead broke. When a representative for one of the wealthy landowners offers him a job surveying an island property to determine its grazing potential and simultaneously letting its solitary tenant know he has to leave, John has no choice but to accept; he is recently married and desperate for work to keep him going until he can establish a new “free” church. Outfitted with a text that will guide him in the delivery of his eviction message, and also a gun, should things go sideways, he makes the long journey to the small, rugged island. But before he even has a chance to approach its lone inhabitant, John falls off a cliff, and it is Ivar, the tenant, who finds him—naked, unconscious and half broken—and brings him to his hut to try to save his life.

John speaks only Scottish and Ivar speaks only Norn, a now-virtually-extinct language once spoken in the Orkney and Shetland islands. Yet they must find a way to communicate if Ivar is to figure out why John is there and John is to make his survey and deliver his eviction speech. And so, over the long period of John’s convalescence, Ivar begins to teach him Norn. And John, previously a devout copier of the gospels, uses the pages that had once contained the eviction text (the words washed away when his backpack fell into the water during his accident) to record them. With every word added to the list, John learns more about Ivar’s life in absolute isolation—and perhaps something about his own shortcomings as well.

Between chapters concerning John and Ivar’s unique and complex relationship, the reader has the privilege of meeting Mary, John’s wife. When she learns that sometimes these evictions don’t go off so well, she decides to travel to the remote island and handle things herself.

This book is so tender, so poetic, so heartfelt, that a plot description cannot do it full justice. Clear is a short, magical, beautiful book, one to read slowly and savor.—JS

R.F. Kuang, Babel: Or the Necessity of Violence. An Arcane History of the Oxford Translators’ Revolution (Harper Voyager, 2022)

Babel is a very British novel, centering on Oxford University and the friendship a group of four students form in the late nineteenth century, as the industrial age moves into full swing during the glory days of the empire. This being (nominally) a fantasy novel, the four students are members of marginalized groups and, in reality, would not have been admitted to Oxford. There are two women, including one of color, a Muslim man from India, and our main narrator, renamed Robin by the professor who brought him as a child from China to England.

China-born author R.F. Kuang, famous from her dark fantasy debut series, The Poppy Wars, studied at Oxford herself. With this novel, she demonstrates her talent for assimilation; she uses a refined sentence structure and advanced vocabulary, in contrast to the thrusting and brutal narrative of her first series. Much of Babel accurately reflects life at this institution during the nineteenth century; the magic concerns only a specific set of actions involving silver bars and translation. However, the idea behind the magic system is totally ingenious.

The four minority students are allowed at Oxford in order to study at the fictitious Babel, an institution for translation and applied magic, because of their facility with languages. That talent is essential to the magic system. Magic is created by the tension between a set of similar words in different languages. The words are almost the same, but as each language has differences in expression, there is a gap between the implied meaning and association of a word in one language and its chosen translation in a second. This isn’t true of every word pair—brilliant and successful students such as Robin graduate to become wordsmiths, finding new pairings between English and the language they are experts in. Each pairing has unique properties that depend on the meanings of the linked words, and most of Babel’s research goes towards finding applications to strengthen the might of the British Empire.

At first Robin and his friends delight in the prestige and comforts of their life in Oxford and the intellectual challenges their work poses, despite the challenges of difficult tests and the occasional insult from the privileged White male attendees. But are Robin and his foreign-born friends truly cherished by Oxford’s professors and the empire, or are they just tools to be turned against their own countries of origin, enablers of the subjugation and exploitation of indigenous people? As Robin wrestles with this question and discovers a secret society of people fighting the use of magic as a tool of colonialism, the novel takes a dark turn, exploring the question of whether peaceful resistance or violent revolution are more effective in bringing about change in the status quo.—GM

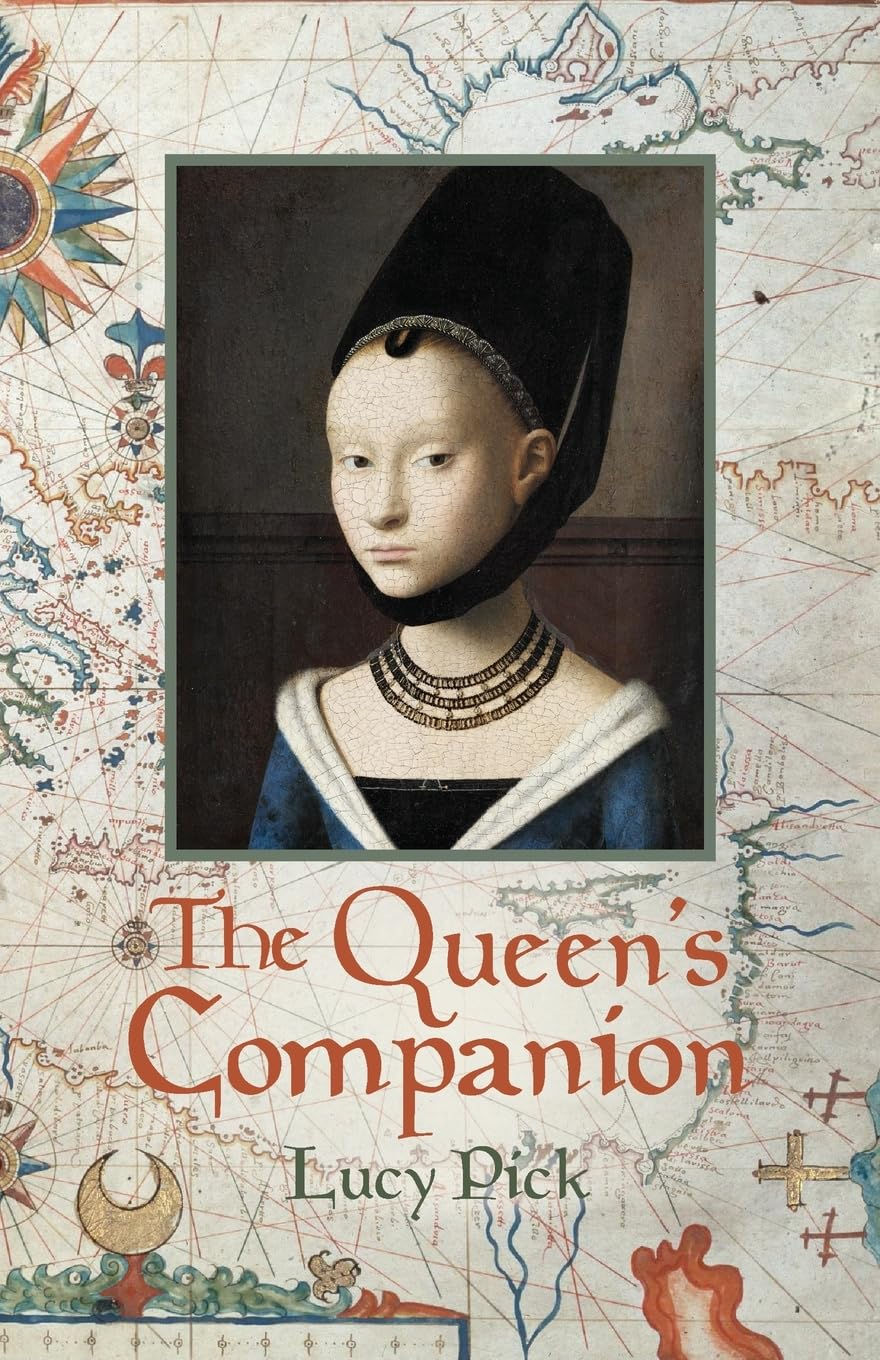

Lucy Pick, The Queen’s Companion (Cuidono Press, 2025)

Eleanor of Aquitaine is best known as the wife of England’s Henry II, the mother of his numerous children—including two kings, Richard the Lionheart and his infamous brother John, of Magna Carta fame—and perhaps for her long incarceration at Henry’s insistence after their burning romance turned to ashes.

What is often forgotten is that Eleanor, before she ever met Henry, ruled as queen of France for fifteen years. About a decade into her marriage, Eleanor accompanied her husband, King Louis VII, on the Second Crusade to re-establish Christian control over Jerusalem, and this is where her story intersects with that of Lucy Pick’s narrator, Lady Aude, who has her own reasons for traveling from Europe to the Holy Land.

Interspersed with the events of the Second Crusade, told from the point of view of the crusaders and witnessed by Aude as Eleanor’s lady-in-waiting, is Aude’s own history, which she presents in the form of stories to Eleanor and her women. Aude is ruthlessly honest in revealing her own flaws and errors as well as her triumphs, and through her voice Lucy Pick creates a character—at times hard to appreciate but always indomitable and even admirable, much like Eleanor herself—who shines a spotlight onto medieval life in all its complexity.

You can find out more from my interview with the author, scheduled to run on the New Books Network in early September.—CPL

Comments